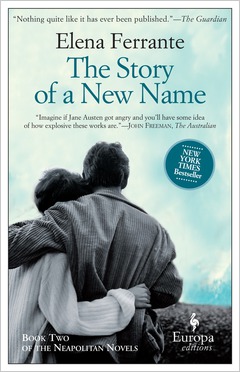

I understood only later that I can be quietly unhappy, because I'm incapable of violent reactions, I fear them, I prefer to be still, cultivating resentment.Indeed Elena (Lena) cultivates much resentment toward Lila in this second of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels, The Story of a New Name.

This novel focuses on Lila, the grocer's wife. It's the story of her marriage, its dissolution, a marriage that was over before it began, as book one had ended with the realization that her husband had essentially sold her out, trading her ideals and ideas, dreams and designs, for some thug's cash and empty promises, a man who'd once wooed her and who she'd sworn would never own her. And it's all downhill from there. This is the story of her miserable married life, with her wretched husband's name.

Elena spends these years preoccupied with the idea of escaping her fate.

Did Alfonso also conceal Don Achille, his father, in his breast, despite his delicate appearance? Is it possible that our parents never die, that every child inevitably conceals them in himself? Would my mother truly emerge from me, with limping gait, as my destiny?Elena holds on to the belief that education is her key to leaving the neighbourhood. For someone who pursues the life of the mind, she is very much trapped by her body.

Suddenly it seemed to me that I had lived with a sort of limited gaze: as if my focus had been only on us girls, Ada, Gigliola, Carmela, Marisa, Pinuccia, Lila, me, my schoolmates, and I had never really paid attention to Melina's body, Giuseppina Pelusi's, Nunzia Cerullo's, Maria Carracci's. The only woman's body I had studied, with ever-increasing apprehension, was the lame body of my mother, and I had felt pressed, threatened by that image, and still feared that it would suddenly impose itself on mine. That day, instead, I saw clearly the mothers of the old neighborhood. They were nervous, they were acquiescent. They were silent, with tight lips and stooping shoulders, or they yelled terrible insults at the children who harassed them. Extremely thin, with hollow eyes and cheeks, or with broad behinds, swollen ankles, heavy chests, they lugged shopping bags and small children who clung to their skirts and wanted to be picked up. And, good God, they were ten, at most twenty years older than me. Yet they appeared to have lost those feminine qualities that were so important to us girls and that we accentuated with clothes, with makeup. They had been consumed by the bodies of husbands, fathers, brothers, whom they ultimately came to resemble, because of their labors or the arrival of old age, of illness. When did that transformation begin? With housework? With pregnancies? With beatings? Would Lila be misshapen like Nunzia? Would Fernando leap from her delicate face, would her elegant walk become Rino's, legs wide, arms pushed out by his chest? And would my body, too, one day be ruined by the emergence of not only my other's body but my father's? And would all that I was learning at school dissolve, would the neighborhood prevail again, the cadences, the manners, everything be confounded in a black mire, Anaximander and my father, Folgóre and Don Achille, valences and the ponds, aorists, Hesiod, and the insolent vulgar language of the Solaras, as over the millenniums, had happened to the chaotic, debased city itself?Life goes on. Lena applies herself to her studies. Lila is her opposite, in every way, in everything.

And then Lena is crushed by love.

I made the dark descent. Now the moon was visible amid scattered pale-edged clouds; the evening was very fragrant, and you could hear the hypnotic rhythm of the waves. On the beach I took off my shoes, the sand was cold, a gray-blue light extended as far as the sea and then spread over its tremulous expanse. I thought: yes, Lila is right, the beauty of things is a trick, the sky is the throne of fear; I'm alive, now, here, ten steps from the water, and it is not at all beautiful, it's terrifying; along with this beach, the sea, the swarm of animal forms, I am part of the universal terror; at this moment I'm the infinitesimal particle through which the fear of every thing becomes conscious of itself; I; I who listen to the sound of the sea, who feel the dampness and the cold sand; I who imagine all Ischia, the entwined bodies of Nino and Lila, Stefano sleeping by himself in the new house that is increasingly not so new, the furies who indulge the happiness of today to feed the violence of tomorrow. Ah, it's true, my fear is too great and so I hope that everything will end soon, that the figures of the nightmares will consume my soul. I hope that from this darkness packs of mad dogs will emerge, vipers, scorpions, enormous sea serpents. I hope that while I'm sitting here, on the edge of the sea, assassins will arrive out of the night and torture my body. Yes, yes, let me be punished for my insufficiency, let the worst happen, something so devastating that it will prevent me from facing tonight, tomorrow, the hours and days to come, reminding me with always more crushing evidence of my unsuitable constitution. Thoughts like that I had, the frenzied thoughts of girlish discouragement.It's a heartbreaking scene; Lena is betrayed by her childhood friend and by her childhood crush. She doesn't see it that way then; she lets is wash over her, and she betrays herself that night.

But ultimately, this is the experience that leads her to write, which solidifies for her a life outside of Naples.

As emotional as the romantic revelations are, what led me to tears was the possibility that Lena's education might be over, "I cried and cried, as if I had carelessly lost somewhere the most promising part of myself," that she might resign herself to a life in the civil service, in Naples.

The title of this book also might apply to Lena as well as it does to Lila. At the end of this volume, Lena's family is examining a copy of her newly published book. Her father recognizes his own name on the cover, but Lena claims it as her own. And even while she is anticipating taking her fiance's name,she intends to keep this name on her future books.

She has found some success, but she's not done measuring it.

I understood that I had arrived there full of pride and realized that — in good faith, certainly, with affection — I had made that whole journey mainly to show her what she had lost and what I had won. But she had known from the moment I appeared, and now, risking tensions with her workmates, and fines, she was explaining to me that I had won nothing, that in the world there is nothing to win, that her life was full of varied and foolish adventures as much as mine, and that time simply slipped away without any meaning, and it was good just to see each other every so often to hear the mad sound of the brain of one echo in the mad sound of the brain of the other.

No comments:

Post a Comment